How could I, someone who loves to read, loves poetry, reach the age of seventy-seven and know so little about the life of Sylvia Plath? I knew “The Story”. That she struggled with suicide, moved to the UK and married Ted Hughes. She suceeded in killing herself when she was thirty. The underlying, always hinted at, current was that she was crazy and brilliant.

When I picked up the Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath by Heather Clark, I’m fairly certain I hadn’t read a single one of her poems. Would I have picked it up (I listened to the audio) if I’d known it was just over 1100 pages? I’ll never know. A friend, a poet, had mentioned her love and admiration for Plath’s poetry in mid-June. I was about to leave on my self-imposed Writing Residency in Saint Jean de Luz (southwest France) and looking for something to accompany me on my train ride, I found Red Comet on Libby and started listening. In reviews that I read while I was listening to the book, it was unanimous that Ms. Clark was presenting the most objective, thorough, story of Plath’s life. Not the dramatic circumstances of her death. In the years since her death, “she has become a protean figure, an emblem of different things to different people, depending upon their viewpoint — a visionary, a victim, a martyr, a feminist icon, a schizophrenic, a virago, a prisoner of gender — or, perhaps, a genius, as both Plath and Hughes maintained during her lifetime.” —Daphne Merkin, New York Times.

Her life, her love of her father, the relationship with her mother who possibly projected all her desires and ambitions onto Plath, her teen years, her internship at Seventeen, and college years at Smith were a revelation to me.

I loved every minute of listening to this audiobook. I found reasons to take long walks just so I could listen to more. The Sylvia Plath of this book was a determined, focused student then young woman who excelled at almost everything she did. She suffered depressive episodes as I did, as so many teens do, yet she remained true to her north star. I was stunned at her singlemindedness of purpose, write and get published. I paused at one point and listened to The Bell Jar. If you ask me why I had never read that book, I couldn’t tell you. But I had avoided it. I found the writing to be lovely, simple, easy to enter into the story and root for the protagonist, Esther. I wanted to know how much was based on her real life. Red Comet told me.

Sitting at my computer in 2025, having lived through the Feminist revolution, the #metoo uprising, all the years where, because of leaders like Gloria Steinham and Betty Friedan, women have come a long way since the 1950s when Plath was writing and advocating for herself, it’s stunning to me how she was able to stand up for herself in the only way she knew how. Her sense of competition was so strong, it drove her forward, but also may have led to her death. She had few female inspirations to look up to.

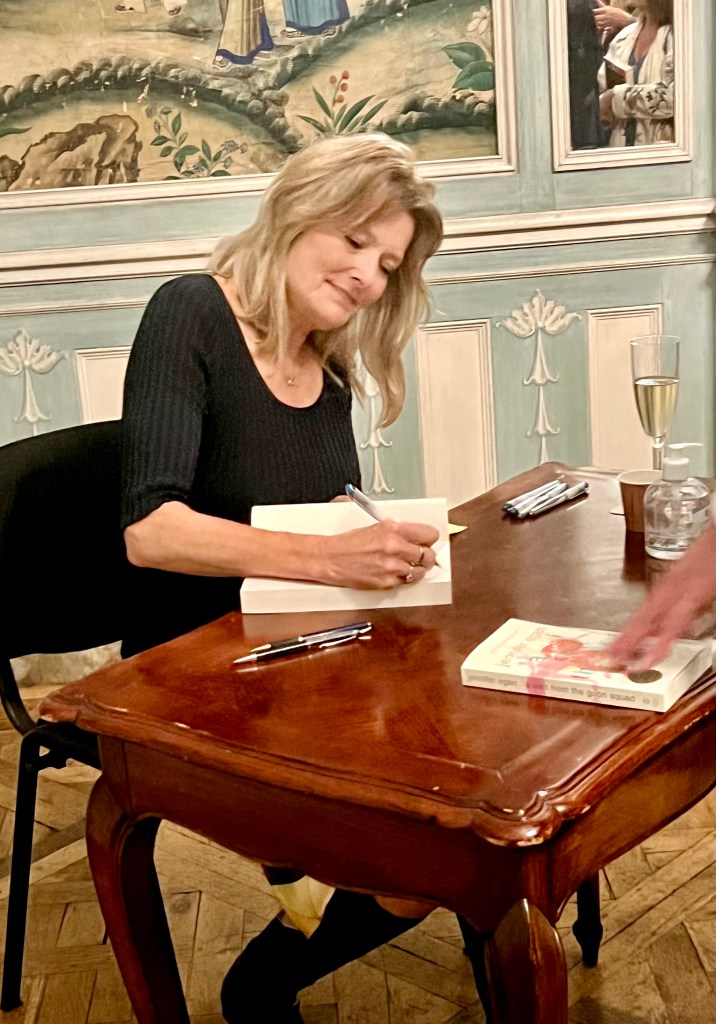

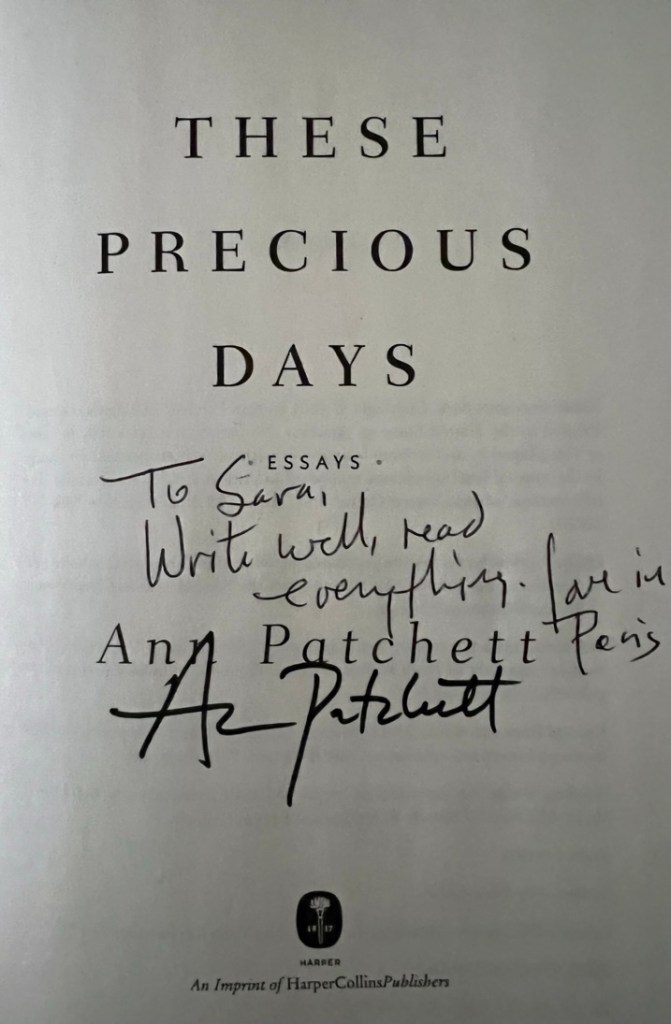

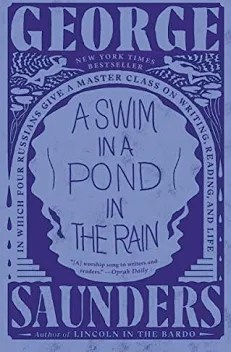

I hadn’t planned to make it a summer of reading feminist powerhouses. For various reasons: wanting to read more essays written by women in order to emulate them; meeting Melissa Febos at the American Library in Paris and getting some positive and encouraging feedback from her, I also read Leslie Jamison’s The Recovering: Intoxication and Its Aftermath (I read Splintering last summer) and Febos’ Girlhood and Abandon Me. Like Plath, both these women take huge risks in their writing, exposing their vulnerabilities, writing from a deeply personal place. Jamison writes about tremendous pain. Febos writes about sex and loving women and her awful childhood of being teased and ridiculed because of her large breasts. Girlhood“dissembles many of the myths women are told throughout their lives: that we ourselves are not masters of our own domains, that we exist for the pleasure of others, and so our own pleasure is secondary and negligible.”—Melissa Hart, OprahDaily.com. Jamison writes about her alcoholism, her lousy choice of lovers and in Splintering, the demise of her marriage.

All three women became professors. Plath at her alma mater, Smith College; Febos currently works as a Full Professor at the University of Iowa, where she teaches in the Nonfiction Writing Program; and Jamison at the Columbia University MFA program, where she directs the nonfiction concentration. In other words, all three women, writing as they do, leave themselves very exposed, unzipped in the world.

As a writer myself, I love knowing these women in depth. Febos and Jamison are alive, young, and headed towards higher accolades than they have already earned. I admire their style of writing. I am in awe of their willingess to expose such vulnerabilities. Jamison is in a twelve step program which encourages self-examination and, therefore, deep shovelling below the surface to face and admit why we do what we do and the consequences. Febos’s work asks us to question every single ‘myth’ we were raised with, every story we were told about who we are and should be, who holds the power in our world and do we, inadvertently, support that world while secretly wanting to have our own personal power.

In the August 4th issue of the New Yorker, Jamison writes about the Pain of Perfectionism. I was struck by so much information, the kind where you smack yourself on the forehead and say “yes, that’s exactly it!”, that I was scrambling to locate on old therapist of mine from California to talk about my personal revelations.

“To Flett and Hewitt (two psychologists she interviewed at length for the New Yorker article), the idea of perfectionism as a form of admirable striving is a dangerous misconception, one they have devoted three books and hundreds of peer-reviewed papers to overturning. “I can’t stand it when people talk about perfectionism as something positive,” Flett told me, as we sat at his kitchen table in Mississauga, a Toronto suburb where he has spent most of his life. “They don’t realize the deep human toll.” Hewitt, a clinical psychologist, has seen with his therapy patients how perfectionism can be “personally terrorizing for people, a debilitating state.” It’s driven not by aspiration but by fear, and by the conviction that perfection is the only “way of being secure and safe in the world.”—Leslie Jamison, The New Yorker August 4, 2025

Read the article.

This summer was an interesting digression for me, someone who loves to escape into mysteries and thrillers. I was revising three chapters of my forthcoming book to submit to a Writing Retreat. I was deep in an attempt to express myself without self-pity, with honesty, with self-reflection, and a desire to show my growth from one period of my life to another. I found inspiration from all three (four if you count Heather Clark, a remarkable writer and researcher) women. They guided me in going deeper, get to the real truth, the truth under what I thought was the truth, the truth that makes me squirm.

To all four of you, I say Thank You.

Thanks for reading Out My Window! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

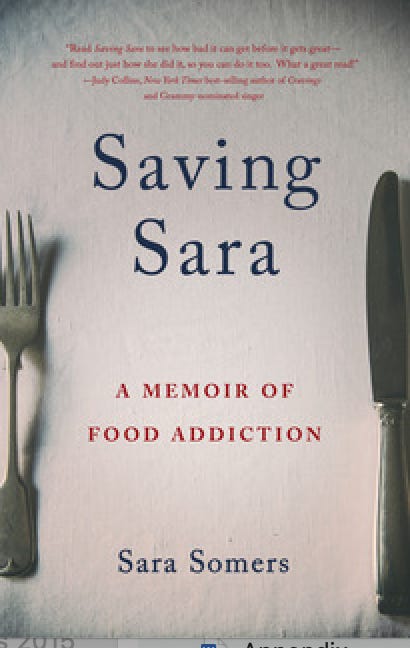

Please remember to go to sarasomers.substack.com and subscribe to Out My Window. I will be shutting down this WordPress blog by the end of the year.

A bientôt,

Sara